Please pop on over to www.angelagilespatel.com to see my new space, and please sign up to stay in touch! Much mad love, -a

It’s happening!

And it’s looking kind of spectacular. My new site should be up within the week, and this site will be retired. To stay in touch, please subscribe to the mailing list here using your email, it’s that easy. I will take care of the rest. I am looking forward to seeing you all over at my new place, I hope you like it….xoxo-a

Change can sometimes be a good thing…..

Some of you know that I have been working on my new website. So far it is lovely, incorporating photography, writing, and other things that make me tick. Keep an eye out for a sign-up post. I do hope you will join me over there, the neighborhood is just wonderful.

xoxo-ap

On Being Me…

On Being Me…

On Writing…

Yesterday, I was asked about the difference between writing what I believe to be the truth versus writing something that can be independently checked. I absolutely think there are differences between personal truths and facts. I also think that there is a line between dramatic embellishment and wilfull lying (which is where Frey and others have erred). My truth doesn’t have to be scientifically accurate or verifiable, that is part of what makes it mine alone. So much of our day to day life is a subjective experience and is conditional event driven…the philosopher in me is quite comfortable arguing that there really isn’t one objective kernel that everyone can agree on, but the scientist in me knows there are some fundamental elements that we can agree on. This is what makes the particular art of the memorist so delicious in my mind, it is the rendering of the world as I find it. Nothing more, nothing less.

On Neruda…

My heart races when Neruda talks of how he sees his lover, how his passion evolves because of her. My heart aches when Neruda shows the profound depths of his depression, how his dark internal world could be. He writes of the world he is experiencing with passion and he does not cloud the essence of his experiences with easy phrases or lofty metaphors. The result is breathtaking.

He once stated that he always returns to his work, “to the blank page which every day awaits us poets so that we shall fill it with our blood and our darkness, for with blood and darkness poetry is written, poetry should be written.” It is this linguistic alchemy that draws me in. His writing insists that I step through the fog of my disbelief and be present as I join him in the rendering.

A task I willingly perform.

I like for you to be still

by Pablo Neruda

I like for you to be still: it is as though you were absent,

and you hear me from far away and my voice does not touch you.

It seems as though your eyes had flown away

and it seems that a kiss had sealed your mouth.

As all things are filled with my soul

you emerge from the things, filled with my soul.

You are like my soul, a butterfly of dream,

and you are like the word Melancholy.

I like for you to be still, and you seem far away.

It sounds as though you were lamenting, a butterfly cooing like a dove.

And you hear me from far away, and my voice does not reach you:

Let me come to be still in your silence.

And let me talk to you with your silence

that is bright as a lamp, simple as a ring.

You are like the night, with its stillness and constellations.

Your silence is that of a star, as remote and candid.

I like for you to be still: it is as though you were absent,

distant and full of sorrow as though you had died.

One word then, one smile, is enough.

And I am happy, happy that it’s not true.

Drifting Beyond The Pale

The essay below appeared on The Nervous Breakdown. I am grateful for the many friends who edited and critiqued this piece. They made me brave enough to hit <send>.

The essay as published can be linked to here.

Drifting Beyond The Pale

My mother is adamant that I was distraught the evening my father committed suicide. I have no recollection of that. She insists I continued to be very upset the next day. I have no recollection of that either. In my mind I was stoic, calm, in control, but the events during that time don’t exist in my memory on any type of continuum or even as full scenes. Rather they are present as moments that stand out against a blurry backdrop, so it is possible she is right. I begin to lose details just seconds after my sister finished saying the three words she had called to relay: “Dad shot himself.”

For an instant, everything slowed down and came sharply into focus. I noticed that the sunlight in my kitchen was sliced by window blinds that were halfway open. The wooden table had ribbons of light and shadows fanned across it and I was aware of how bright and warm it looked outside. Then everything shifted. My apartment felt cold and when she repeated the sentence, the words became a roar, each one echoing in my head. The confusion lifted quickly. Then everything shifted again, as the words took on meaning. The roar quieted. The ribbons disappeared into simple shadows. Nothing beyond the window looked bright. As much as I wanted to reverse time to the moments before I answered the phone, so I could linger in what ‘before’ felt like, I found myself propelled forward by events well out of my control.

The one instance I know I displayed unrestrained emotion was when we were deciding on the wording for the headstone that would mark my father’s grave. My sister thought it should read “In Loving Memory” and I thought it should read “In Fond Memory.” It was a shouting match that brought us both to tears. I was forceful and angry. She was outraged and determined. She argued that you are fond of dogs, that you love fathers. I argued that loving fathers don’t abandon their children. We were both right.

My father was an active alcoholic. I have no awareness of a time when alcohol didn’t factor into our lives in one way or another. Every element in our house revolved around my father and his disease. My sisters and I grew up understanding that while we were loved by our parents, neither was dedicated to the task of raising us. So we took care of ourselves when we needed to, and, as circumstances required, took care of him. On any given day, he was more likely to be drunk than sober. We grew up learning to anticipate my father’s condition and adjust our behavior. We developed a remarkable ability to gauge the mood of our house by smell. To this day, I can single out a vodka drinker in a crowded elevator.

The vigilance we felt obligated to maintain was even more intense outside our home. My father would show up intoxicated at some events we were participating in, and be sober and fully present for others. There wasn’t a pattern, so we were never able to predict what would happen. We learned to be prepared for anything. Our sole priority was to control the secret of his alcoholism as much as possible. As a result, I never had the thrill of feeling protected and carefree. Growing up early robbed me of an understanding that vulnerability is not a failure and trust is not a weapon.

Still, he was my father. And I loved him. I loved him so much that I thought it would be enough to change him. We all did. Giving up on him was never an option. Perhaps it was seeing my mother refuse to give up on him, as well as the feeling that there was something we could do to fix him, but we never accepted that the disease was stronger than we were. We never accepted that it was solely his battle to fight. We were wrong.

I spent time with him six days before he died. It was late January and the divorce my mother filed for was finalized earlier that same month. He had moved out of the house and found a temporary place to live. I was twenty years old. He was forty-eight. We had spoken on the phone, a couple of times in fact, but I needed to see him. I had no particular reason to want to see him, just a solid need. So I skipped classes, drove the three hundred miles south, and met him one evening after he was finished with work.

The drive was uneventful—that is to say I honestly have no memory of it. I am sure there was a cd playing, I’m sure I was mindful of the traffic, I’m sure I had snacks or at least a soda with me. I’m also sure that I was preparing for whatever I found when I saw him. Bracing myself was second nature when it came to my father, I was used to him at his worst. Given that he had been made to leave the house he loved, agreed to end his marriage, and now had to look for a way to start over, his worst is what I expected to find.

The motel he was staying at was conveniently located near the only liquor store in town. It was also close to a supermarket as well as to the printing shop where he had managed to keep his job for years, primarily because of the kindness of the family who owned it. When it came into view, I signaled a left turn and entered the parking lot.

Made of cinder block and painted white, the single-level building had warped plywood doors and red trim around the windows. The trim was peeling off in thick, matted chunks. The tattered marquee listed only weekly rates. Smoking and non-smoking rooms were available. The neon vacancy sign was lit. Even the asphalt was cracked. The outside reeked of decay, of travelers who’d ended up there, most out of options and many also out of time.

I parked my car. Turned off the ignition. Gripped the steering wheel. Closed my eyes. I hated that I was visiting my father in this dismal place. It was the type of motel people went to when they had nowhere else to go. I took a breath, grabbed my bag and gave myself one quick look in the rearview mirror. I needed to look composed, and I did.

I stepped out of the car, guarded, cautious, ready to be expressionless if I saw a marked deterioration when he opened the door. Then I knocked. He opened the door before I finished knocking. But he wasn’t drunk, he wasn’t angry, he didn’t even seem particularly depressed. He was happy to see me and asked me to come into the room. I was happy to see him sober and entered.

The room was poorly lit and appeared especially gloomy because of the wood paneling on all four walls. Clothes were draped over the only two chairs, pants on one, shirts on the other. The bed was partially made. It was clear he was sleeping on the right side of the bed, the other side looked untouched. I remember thinking how odd it was that he wasn’t sleeping on the left where he should have been; instead he was sleeping on my mother’s side. He began taking clothes from the chairs so that we could sit and talk. I could see his hands shaking as he tried to make a place to sit. I said it was okay, that we could just sit on the bed.

So we sat. Side-by-side. My bag near my feet on the floor. Both of us facing the dusty window. The curtains were open, but it didn’t make a difference. Based on the amount of light it gave off, the lamp on the nightstand was for decoration only. The cheap plastic ashtray next to the lamp needed emptying. I saw a collection of blood-stained tissues in the small garbage can on the floor next to the bed. It was not unusual for my father to have nose-bleeds, he’d had them for as long as I could recall. They are a common indication, I later learned, of alcoholism. I wondered just how much he was drinking now that he was not home. The threats of leaving, of making him leave, were issued for years. The drinking didn’t stop. Then suddenly the threats were no longer empty and here he was. Though there were no signs of alcohol in the room, the air inside was heavy with vodka and smoke and perspiration. It was a nauseating, diseased smell. I hadn’t lived at home for nearly three years and had forgotten what it was like; the room smelled like my childhood.

We began to talk. It was more small talk really. He wanted to hear all about my classes (liberal arts focused), my grades (outstanding), my boyfriend (going well), my part time job (not too stressful). The conversation was not tense, not at all difficult. If a stranger overheard us speaking, it would have sounded like a typical father and daughter chat, perhaps it would have even sounded boring. But it was far from casual. In the midst of talking, I tried to take in all of the details in an attempt to make sense of what had happened with my parents. It made sense that after years of living with an alcoholic, my mother could no longer accept the disease. It made sense that they divorced. It made sense that he moved out and came to live in this nameless place. It all made sense, but none of it seemed real. It felt out of my control and unlike when I was younger and everything that happened in our house was kept in our house, events had been set in motion that would have implications in the world beyond our front door. I needed to see him that day to determine what the implications would be. I was assessing everything about him, his body language, his speech, the state of his clothing. I wanted to memorize every detail.

The conversation trailed off and I stood up and moved toward the small writing desk. It had a mirror hanging above it that was as tired-looking as everything else in the room. My back was to my father but I could see him in the mirror’s reflection. He was still looking toward the window. We were both quiet, him staring outside, me staring at him in the mirror. I saw his head turn toward me. I lowered my head before our eyes met in the mirror.

I stood there.

Still.

Listening.

I don’t remember any of the sentences he spoke, just phrases: “my drinking,” “everyone tried,” “my fault,” “I love your mother,” “proud of your sisters,” “proud of you.” I didn’t want to create the slightest disturbance in the flood of words. I didn’t want it to stop. And I didn’t want to cry. So I focused on tracing the lines of the telephone with my finger, feeling the spaces between each button. Just as abruptly as he started speaking, he stopped.

It was still daylight when we stepped outside. The fresh air and sunlight felt almost overpowering. Even though the dark room was stifling, it felt familiar. My father had always smoked, but he never smoked inside at home because we were around, so it was second nature to both of us to head outside if he wanted a cigarette. He took the lighter from his pocket, but before he lit the cigarette, I wrapped my arms tightly around him. I buried my head in his shoulder and held on. He held on just as tightly. I wanted to breathe him in, to imprint the smell of sweat and newsprint and nicotine on my brain. I told him I loved him before I finally let go. Then he let go.

He lit his cigarette as we said goodbye. There were no assurances passed between us, no half-hearted plans to meet again. He actually thanked me for coming. I wanted to say “Of course I would come” but I didn’t. When he thanked me for coming, I knew. In that moment I realized that sometimes love can’t outrun disease, no matter how much you want it to, and there was absolutely nothing I could do. I got into my car with the realization that I was seeing my father alive for the last time.

I have no idea if he had already planned his course of action when he spoke to me that day or if it was more spontaneous. Less than a week later he would park his truck outside the house he had lived in for more than fifteen years, turn off the ignition, remain seated behind the wheel, rest his right temple against the barrel of a rifle and pull the trigger. Just like that, it was over. He left no note.

It wasn’t a jolt when he died, it was more of an extended boom, like elements inside me suddenly realigned. I alternated between feeling as if my core was being scraped raw by a jagged knife and feeling as if I were being siphoned away from somewhere deep inside. And as much as I recall the jumble of moments leading up to the funeral, looking at his body, pulling my sister from the casket so they could close it, I can’t recall showing any outright emotion beyond fiercely efficient tears. The fact of his death washed through me, leaving no cell untouched. Days were marked in degrees of ache, not by any calendar. I took nearly a month off from school, and my time was spent slowly catching up to the rest of the world. By the time I went back, I had perfected the art of detached storytelling, a quality that many still find unsettling, and I had learned how to function with a hole inside of me.

My father has been dead for more than half my life, but I suspect I will always feel the vibrations created by his suicide. There is no getting over it; his death wove itself into my fabric. I live in a shadowy place where fathers leave, where fathers choose to leave. I also live in a place where time definitely does not heal wounds, where it doesn’t even try. Part of me will always be stuck in that parking lot, feeling powerless in the face of his end. On my worst days, I am the girl who wasn’t good enough to keep her father around. On my best days, those smeared together events are so far in the past that it feels like a different lifetime. Most days I am somewhere in between, feeling broken but not irreparably so…furiously focused on keeping myself steady in the ripple he created. Afloat on such pain that I still find it hard to simply cry.

The Photographer

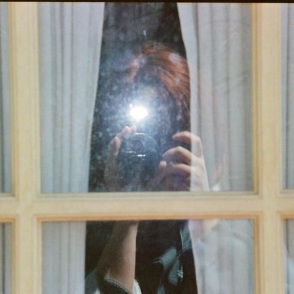

I have no idea why I took that picture.

It’s not very clear and the glare from the flash is prominent, a powerful circle of light just up from the center of the shot. I exist in the photo as a glazed image, an echo neatly sliced by windowpanes. You can’t see anything through the glass except for the curtains. The white cloth is separated and the room that would open up behind it is not visible. The flash of light has turned a clear pane reflective and it takes a minute to realize that in the photo I am on the outside, looking in.

Featureless except for the red hair, you can see three fingers from my left hand wrapped around the side of the camera, with my index finger on the shutter button. My right hand is curled under the lens, keeping it steady. Based on the placement of my hand, I appear to be manually adjusting the focus. A small attempt at exercising control. It is a hazy image and had it been taken any other day, I would have thrown the photo away as nothing more than a strange mistake. But it wasn’t taken on just any day. This picture is the truest image of me in the hours after I learned that my sister died.

The remaining pictures on the roll of film are of the flowers that had bloomed just days before, and that was my intent in loading film in the camera that morning – to take pictures of the garden I had planted. I’m not a talented photographer, but I enjoy trying to capture the world as I see it, to save moments I find meaningful. So, on that morning, I slowly moved around the perimeter of my house. I looked at light and shadows and lines. I surveyed the richness of color before me and felt unmoved. The flowers had lost their charm even at their peak. Still, I studied my subjects, touching the petals, moving in to smell the bloom, tracing stems with my fingers. Then I began taking photos.

A single daffodil.

A line of tulips.

A bunch of hyacinths.

Blades of grass.

I used different filters, adjusted the focus to blur flowers or background or both. Crouching and twisting, I maneuvered my body on the grass. Beyond the chill the dew gave me, I felt nothing but the need to take pictures. I had a nervous, almost urgent energy, as if I were racing some unseen clock and had a small window of time to try to record their bloom. The variety mesmerized me. The shadows understood me; I too was separate and transient and dark.

I shot three rolls of film in less than thirty minutes. Each click on the camera was a deliberate and controlled act. Picture after picture after picture.

Today, when people see the vibrant images hanging in my kitchen, they ask if I took them.

I tell them yes I did, they are flowers at our old house.

I tell them that I spent hours planting hundreds of bulbs.

I tell them that I preserved the flowers I had planted the only way I knew how, on film.

I do not say I needed to save something exquisite that had moved me.

I do not tell them that I needed to freeze beauty in hopes that one day I would again recognize it.

I do not tell them that the day my sister died, I took pictures of my world.

On My Love of Rilke…

Rilke can utterly undo me. He has the ability to help me clear my mind — trust me this is no easy task. I don’t know if it is the sensual imagery, the stark mysticism, the rigorous language, or all three.

I suspect it is all three…

The Book of Hours, I, 17

She who reconciles the ill-matched threads

of her life, and weaves them gratefully

into a single cloth—

it’s she who drives the loudmouths from the hall

and clears it for a different celebration

where the one guest is you.

In the softness of evening

it’s you she receives.

You are the partner of her loneliness,

the unspeaking center of her monologues.

With each disclosure you encompass more

and she stretches beyond what limits her,

to hold you.

-Ranier Maria Rilke